GLOVERSVILLE — Feb. 20, 1945 was the second day of the Battle of Iwo Jima, a five-week U.S. invasion of the island during World War II.

Ambrose “Cowboy” Anderson of Gloversville, who died late last month, had just arrived on the Pacific island.

It wasn’t his first experience taking on the Japanese — and it wasn’t his last. On his trip to the island, feeding ammunition, he helped defend his boat from a Japanese kamikaze aircraft.

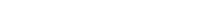

At the time, that was an illicit action because the gunner was white and the 19-year-old Marine from the Glove City was one of the nation's first Black Marines.

“He would have been stimulated by all of the same stimuli as the white Marines, but he had this other battle going on,” said Mark Yingling, an advocate for Iwo Jima survivors. “[Black Marines] were treated less in every aspect of their life, starting with the trip to boot camp.”

The Gloversville High School football star was drafted into war in 1943. He was forced to sit in the back of the bus en route to Montford Point, an all-Black boot camp in North Carolina. There, he was harassed by white recruits, including his captain, while living in a shack.

Such discrimination, Yingling said, pushed Black Marines to prove themselves in combat.

In Iwo Jima, Anderson was one of nearly 900 Black infantrymen to hit the island.

More than 70,000 Marines were involved in the invasion, 6,140 of which died in battle.

State Sen. James Tedisco presents World War II veteran Ambrose ‘Cowboy’ Anderson, who served during the U.S. invasion of Iwo Jima, with the New York State Liberty Award in front of the Forest Hill Towers in Gloversville, Friday, Aug. 28, 2020.

“I knew I was in a war when I saw Marines floating in the ocean and when I hit the beach and saw a Marine get his leg blown off,” Anderson told the Daily Gazette in 2020.

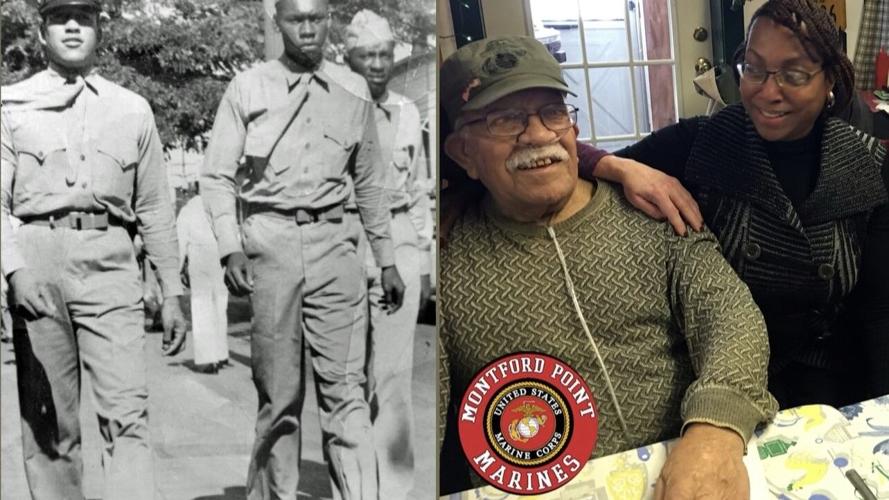

Anderson was one of three greater Capital Region veterans remaining from the fight before he died at the age of 98. About 10 years ago, there were more than a dozen men left.

“Of course, the number you're losing is going to drop, but these guys are defying the odds,” Yingling said. “Some of the Marines I knew were engaged in multiple invasions, had multiple wounds and still survived into their late 90s.”

It’s not certain how many Montford Point Marines are left. Yingling expects that the number is scarce.

More than 20,000 Marines were stationed at Montford Point from 1941 to 1949. The military wasn’t fully integrated until 1950.

Meanwhile, Anderson’s experiences with segregation left a mark at first.

“The way they treated us, I came back bitter,” Anderson told the Daily Gazette in 2020. “Things got better, but we are still not there.”

Anderson’s return home had little fanfare. Black soldiers didn’t reap the benefits of the GI Bill, which provided opportunities for veterans.

After struggling at first, he eventually nailed down a job as a truck mechanic at Ryder. He went on to have six children, including four with his second wife of 47 years, Betty. She died in 2004.

The intitial feelings of bitterness didn’t last, Yingling said.

“You would think it would be a change that involves great bitterness and hatred, but I don't think he was capable,” Yingling said, “and I attribute that to his long life.”

Anderson, who went on to serve during the occupation of Sasebo, Japan, wasn’t widely recognized for his service until later in life. In 2011, he earned the Congressional Medal of Honor and nine years later, the state Senate’s Liberty Award.